pseudorandom

Code Style

What is code style?

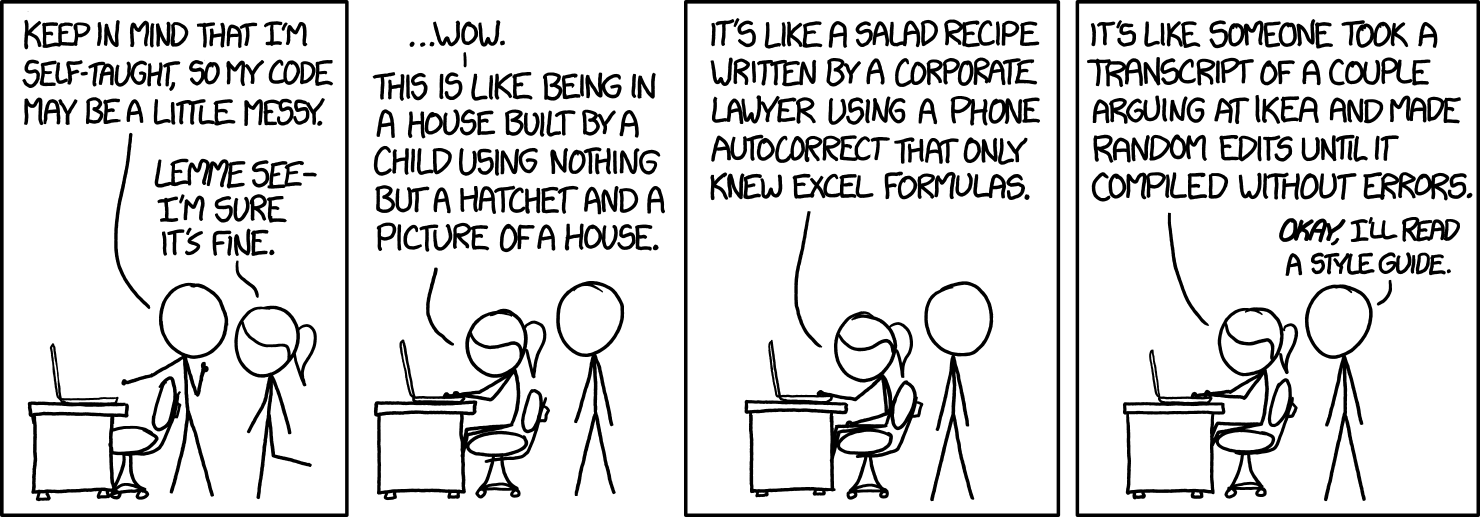

Code style is a term of quality used to describe code that is authored to be readable and comprehensible. This quality does not come automatically or by accident to anyone (not even you, dear reader), and is the result of effort a programmer takes to make his or her code easy to read and reason about. It is an essential component of creating a codebase that is maintainable. ‘Style’ includes naming conventions, systems of organization of logic, priorities for an engineer to take when writing code, and so on. Writing code with a good style is an important element of being a good engineer, and essential to being a good teammate. Code produced with a good style lives beyond the original writer and provides overall benefits to the codebase; not just short-term stopgap solutions. As such, the degree of cleverness or “coolness” that code has does not represent code style (quite often the inverse — very clever code can often also be unreadable).

Why is code style important?

There’s two important things to consider:

- the vast majority of an engineer’s time is spent reading other people’s code.

- the average human can only retain 3-4 data “chunks” in their short-term memory at one time.

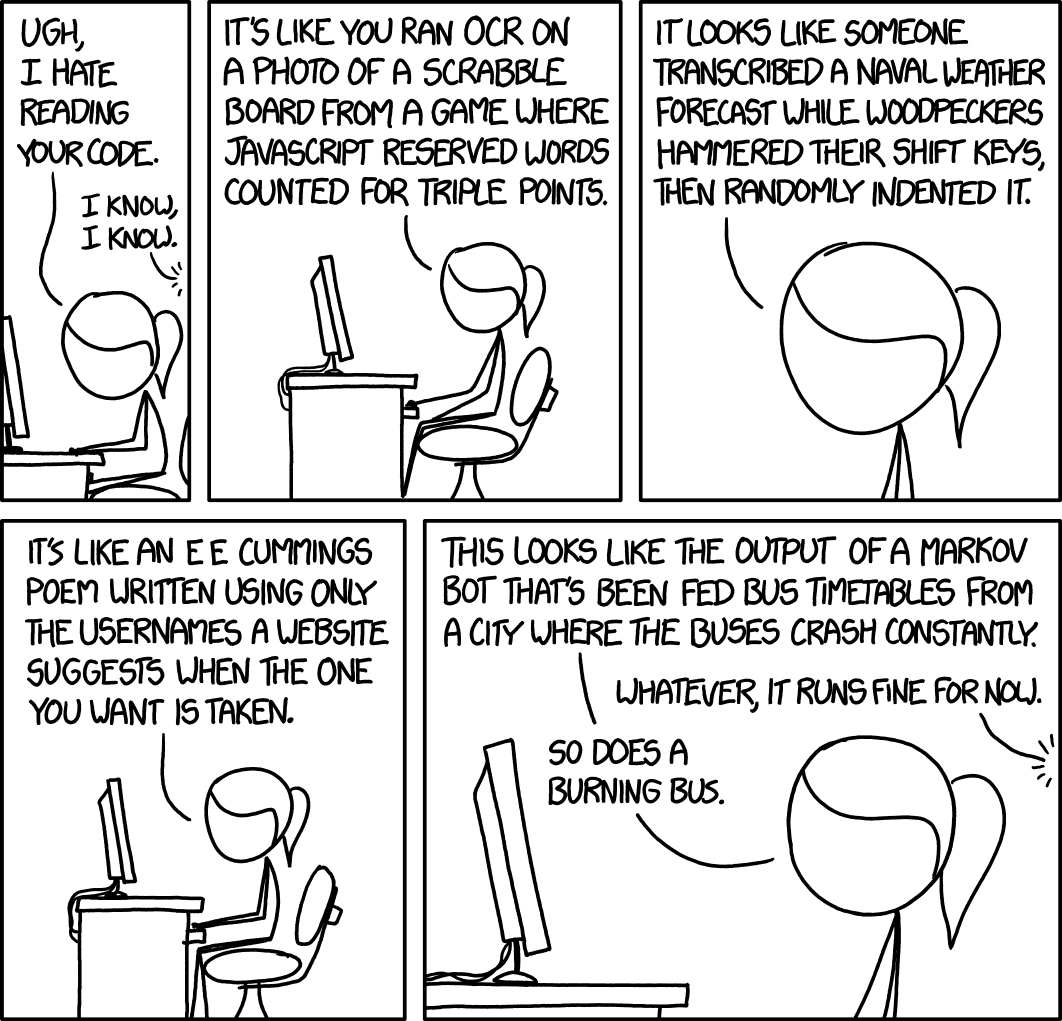

You can think of clear and understandable code as a multiplier upon those two properties. The clarity of code can increase or decrease the amount of time spent reading, and how many times you have to go back to understand what’s going on in order to pick up links of a too-long logical chain. You should always remember that other people will be reading your code; in fact, you yourself will often come back to your code not remembering how it works. For this reason, consistency and cleanliness are top priorities when coding. It’s not just “nice to have” – code without consistent and clean style is a net negative: it drains the productivity of everyone who comes across it.

Let’s analyze what goes into good code style:

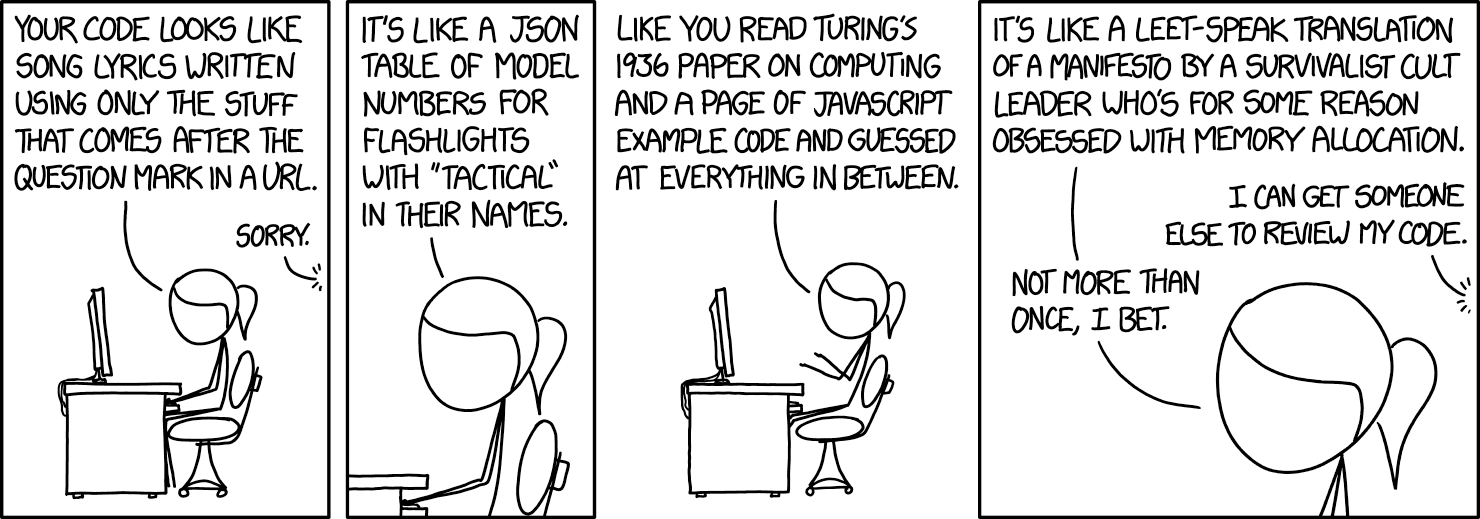

- Consistency: if all code is arranged and organized predictably, reads in the same manner, and is named in a consistent way, the engineer reading can understand more quickly. Though a reader may often blame themselves for having to go slowly through chains of reasoning, inconsistent coding styles require a surprising amount of cognitive overhead to switch between. Imagine trying to find information in a reference book that was cobbled together from multiple personal notebooks – how do you find what’s important? How do you avoid needing to read all the irrelevant information in each chapter just to get the information that you need? That’s what we’re doing day-to-day while maintaining a large code base; and recall that with only 3-4 data chunks available, a “miss” is very harmful to productivity as it can initiate extra rounds of laborious searching.

- Cleanliness: code should be separated into small functions that do one thing and do it well. By doing this, we can think in abstract terms about the way code works, and much more easily navigate it without dedicating a chunk of human memory to just keeping track of side effects, edge cases, and specific context. Your function code should read like a story: this function does this, than that, than that. If this happens, that occurs. By thinking in terms of separated functions, we can reason about existing code more accurately, navigate faster, test more granularly, and our code is easier to read.

- Human Centricity: code should be written for the purposes of being read by another human as opposed to the computer. The degree to which intent is clearly described is also the degree to which a reader will be capable of quickly understanding the ideas in the code. As such, a series of random steps is often much worse than an abstraction or a more lengthy description of concepts.

Before you submit anything, it’s important to always go back over your code from the perspective of a new, junior hire. If they had to review your code, would they understand it? If they ran into your code while trying an early project, would they be able to get to the important stuff quickly? Again, recall that we only have 3-4 data chunks available: each time we demand attention, we take at least one of those away from what is otherwise very important stored memory. Moving from one section of code to another is similar to calling a function from another. It creates a totally new context, requires bringing along exactly the right data to that context, and ultimately needs the correct data be returned back up the “call stack”. When someone needs to trace your logic through multiple contexts without guidance there is always the chance that they will hit a moment of “wait, how did that work again?”, metaphorically return null, and start a frustrating loop of re-reading previous code. Your logic should trace through steps that not only feel appropriate, but inevitable. Use functions and abstractions to allow the reader to understand a concept and build off of it quickly.

Why is code style not the same as lint?

Linting is an automatic way to test some elements of style. Because it’s automated, it necessarily excludes anything that requires more qualitative judgement, and replaces it with granular quantitative metrics. For example, because lint fails on a 15 statement file doesn’t mean that you should just reduce it to 14 – it’s a signifier that the area itself likely has bad code style. It means that you should seriously consider refactoring that function, or even the entire scope of where it is used or farther. Another example is in naming conventions — lint is unable to know if things are named consistently and in an appropriate manner. Lint helps us in that it points out where we have potential problems, and it can sometimes automate the fix when those problems are simple enough (for example, if your spacing is out of convention). It’s really important that you regard code style itself to be only semi-enforced by lint, and that constant cognizant effort is important and necessary to maintain good style. Once again, good code style doesn’t happen by accident.

Recommendation

I strongly recommend Airbnb’s and Google’s code style documentations:

Please contact me for any thoughts, comments, or feedback.

author: "Aaron Buxbaum",

email: "me@aaronbuxbaum.com",

github: "github.com/aaronbuxbaum",

linkedin: "linkedin.com/in/aaronbuxbaum",

}